Behind the Costume

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X04mkEXA0Tg Cosplay telah menjadi fenomena di Indonesia selama 10 tahun terakhir sebagai bagian dari budaya Jepang kita. Banyak acara Jepang memasukkan cosplay sebagai salah satu acara utama mereka. Mereka bahkan mengadakan kompetisi yang juga dikenal sebagai cosplay walk. Hal ini juga menunjukkan bahwa budaya cosplay sudah menjadi hal yang besar di Indonesia, dan ada banyak cosplayer kompetitif dari Indonesia yang berpartisipasi dalam kompetisi cosplay tingkat nasional atau bahkan internasional. Film yang kami buat adalah tentang perjalanan seorang cosplayer pemula yang tidak tahu apa-apa tentang budaya cosplay sejak awal hingga ia menjadi cosplayer dan bagaimana hal itu mempengaruhi kehidupannya secara umum. Kami mencoba mengedukasi pemirsa bahwa semua orang bisa masuk ke cosplay, tetapi tidak semua orang bisa menjadi cosplayer. Dari kostum, makeup, properti cosplay, memperdalam karakter yang kita mainkan. Upaya kami untuk mendorong dan memotivasi terutama cosplayer pemula dan orang-orang yang ingin mencobanya dengan menonton film kami sehingga mereka sadar bahwa tidak perlu takut untuk melakukan kesalahan karena ini adalah bagian dari proses yang panjang.

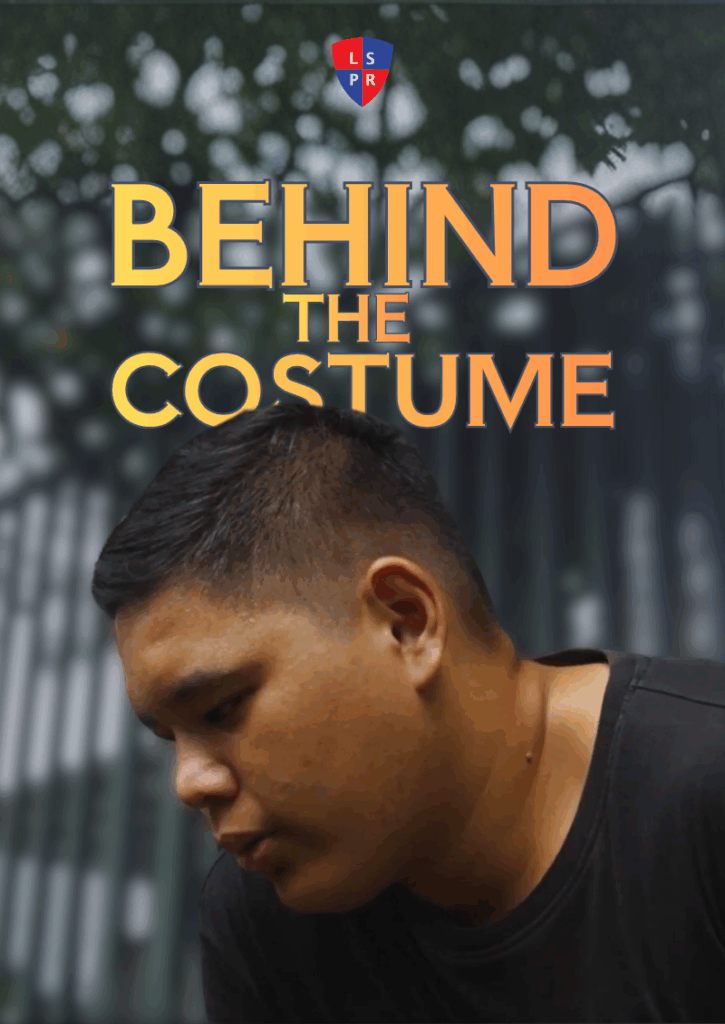

Cultural Abuse: Ondel-Ondel

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fx7mjZd-xW0 Through the documentary film “Cultural Abuse: Ondel-Ondel”, we want to highlight this issue using a concrete example: a cultural icon of Betawi. Ondel-ondel is a Betawi cultural icon that has long symbolized the identity of Jakarta’s people. It represents the richness of local culture, especially in traditional performing arts. Unfortunately, in recent years, ondel-ondel has shifted from its original function as cultural entertainment to being used for begging on the streets of the capital. This phenomenon is concerning because more people—especially the younger generation—are growing up seeing ondel-ondel not as a cultural heritage, but as a symbol of poverty and economic exploitation. This situation points to serious issues around cultural preservation and the need for decent livelihoods for traditional artists. Street ondel-ondel performers sometimes even involve children who go door to door to beg. This marginalizes the original meaning of ondel-ondel, while also showing they lack adequate access to decent work and sufficient income for a dignified life. According to a 2022 Jakarta Good Guide report, about 60% of ondel-ondel street performers are not traditional artists but people using ondel-ondel as a way to make money because of economic hardship. In fact, in 2020, the Governor of Jakarta issued a ban on street ondel-ondel performances, seeing them as a misuse of cultural heritage. This documentary tells the story of how ondel-ondel, once a proud Betawi cultural symbol, has become a means for some in the big city to earn a living. This change reveals the harsh economic reality faced by lower-income communities who feel they must use culture as a survival strategy. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion

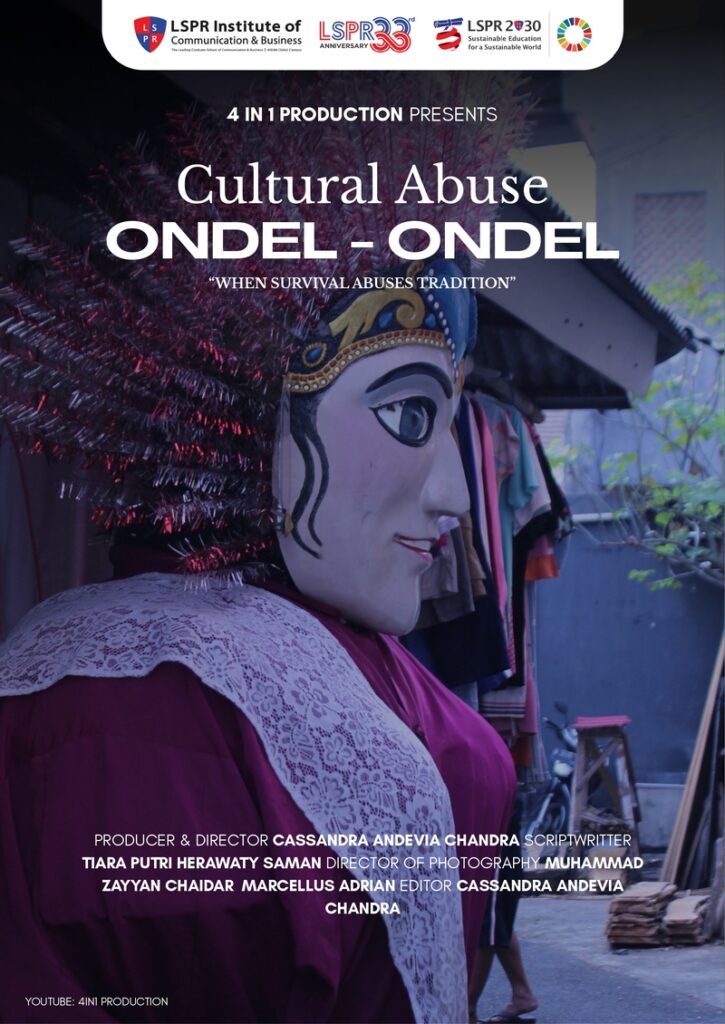

Bound By The Sea

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PF9AeLX_LA0 Behind the massive growth of the fishing industry, there is a dark reality experienced by many Indonesian crew members (ABK/”Anak Buah Kapal”). They are often victims of the labor crisis and economic growth; exploitation, forced labor, physical and psychological abuse, and other human rights violations. Many crew members work up to 20 hours a day without proper wages, lose their right to salaries for months, and even experience inhumane treatment, such as dumping bodies overboard without following international procedures. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 8 emphasizes “Decent Work and Economic Growth”. The goal is to promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all. Reporting from the KIME FEB UNNES website, BPS (Central Statistics Agency) data for August 2024 recorded that 31.94% of the workforce were not full-time workers. This shows that almost a third of the total number of workers in Indonesia do not do their jobs with standard working hours. These non-full-time workers consist of 34.63 million (23.94%) part-time workers and 11.56 million (8%) underemployed workers. Part-time workers refer to those who work less than 35 hours per week, while the underemployed are those who are employed but still looking for additional work or jobs with more hours. This condition shows that most Indonesians are currently not fully employed and do not meet the criteria for decent work according to the ILO (International Labor Organization). Then, according to data from the BPS (Central Bureau of Statistics) publication “Decent Work Indicators in Indonesia 2023 Volume 7, 2024, 41% of the workforce in the country has formal jobs, while the other 59% work in the informal sector. Formal employment includes labor contracts, social security, and good working conditions, while informal employment often does not provide adequate protection or workers’ rights. Due to inconsistent enforcement of regulations, existing labor regulations are often poorly implemented. Lack of supervision and enforcement means that many informal workers are denied basic rights such as health insurance, job security, and pensions. The data above shows that employment conditions in Indonesia are still poor and can affect sustainable economic growth in Indonesia. One of the issues that we will raise in the documentary film that we will make is the issue of providing inadequate employment for ship laborers or crew members (ABK) in the new Muara area. It is known that the crew members in the new estuary harbor do not get their rights as workers. They often do not get the salaries promised by ship owners who hire their services. Even if they are paid regularly, the salary is not commensurate with their hard work. Crew members are also vulnerable to labor issues; exploitative working hours often exceeding 7-10 hours a day, unsafe and unhealthy working conditions at sea, illegal and non-contractual recruitment, and the practice of body-slinging. Reporting from the website www.greenpeace.org, regulation of shipping work in the country of Indonesia is still considered not optimal, so that the provision of unfit employment for ship laborers often occurs. As evidence in 2020, the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union (SBMI) received 104 complaints related to slavery and forced labor experienced by crew members at sea, which number increased from 2019, of 86 complaints. Therefore, this issue was chosen because it is very relevant to efforts to achieve SDG 8 and is a clear reflection of the failure of the labor protection system in the fisheries sector. In addition, Indonesia, as a maritime country with a large number of fisheries workers, has a moral and legal responsibility to protect crew members from forced labor and exploitation. One organization that encourages such protection is Greenpeace Indonesia, which is part of a global environmental organization. Greenpeace was founded in 1971 in Canada by a group of activists who opposed nuclear testing in the American state of Alaska. Since then, Greenpeace has developed into an international organization that focuses on environmental protection through non-violent direct action and public campaigns. The push for ratification of ILO Convention 188 has also been echoed by civil society organizations, including Greenpeace Indonesia. Of the 11 ASEAN member states, Thailand is the only one that has ratified and adopted ILO Convention 188 (K-188) into its legislation. While K-188 sets minimum standards of protection for fisheries workers, Indonesia lags behind in adopting and implementing them. Voicing deep concern over this condition, Greenpeace Indonesia urges the ratification of ILO Convention 188 because this convention is an important instrument to protect the rights and dignity of workers in the fisheries sector, especially crew members, who have been vulnerable to forced labor practices, exploitation, and human rights violations. As a form of support for this call and an effort to raise public awareness, we raised this issue in a documentary film, hoping to open the eyes of the wider community to the importance of protection for crew members. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion

Vicara : Connecting The Unlooked

https://youtu.be/g0RxAYNCDuA?si=TJG4m1n2Y7S8A9PF This is based on the belief that every individual, including children with autism, have the same right to communicate, socialize, learn, and understand their surroundings. Communication is a process of exchanging information, ideas, feelings, and messages between two people or more. In addition to that, communication is also a tool for self-expression. But for children born with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), the right to communicate both verbally and nonverbally is often limited by stigma and lack of understanding from society. According to the data from the World Health Organization (WHO) website. In the year of 2023, it is predicted that 1 out of 100 children have autism. However, Indonesia does not yet have definitive data on the number of individuals with autism. Autism-Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by repetitive behaviors and difficulties with communication and social skills development. With the further growth of technology, especially image-based and voice-based communication applications, it has brought new hopes. Applications like VICARA, developed by the London School of Public Relations (LSPR) Jakarta and ICT Watch Indonesia, provide picture communication cards that have audio using Text to Speech technology. The application is designed to help children with autism learn to communicate and recognize everyday conversations, so that they can interact with a more inclusive environment and grow in confidence. We believe that communication is not just someone’s privilege, it is a basic human right, VICARA is here to ensure that all voices deserve to be heard and understood. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion

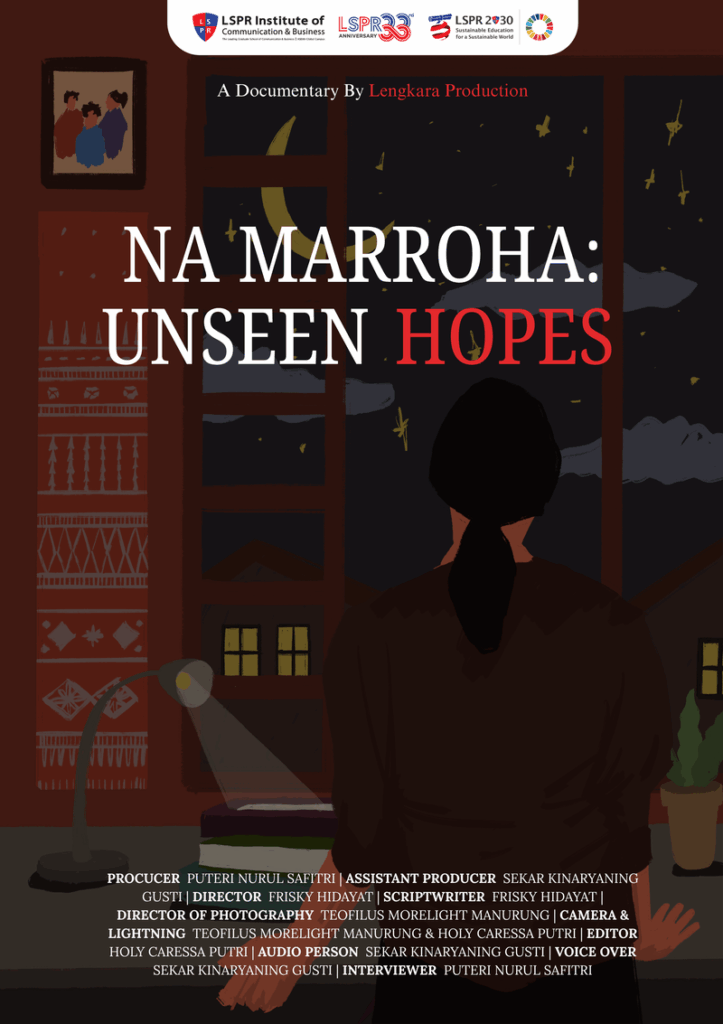

Na Marroha: Unseen Hopes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YlhzfZRxLAo This proposal is developed with a specific focus on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: Good Health and Well-being. The primary aim of this SDG is to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO): “a state of complete mental, physical, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (Chapman et al., 2017). SDG 3 consists of nine sub-targets, including the reduction of mortality rates among vulnerable populations, the control of communicable and non-communicable diseases, the promotion of mental health, the prevention of substance abuse, the creation of universal health care access, and the strengthening of health systems. Based on these goals, we emphasize one of the key factors influencing community and family well-being: mental health. Furthermore, we explore how access to quality education, when aligned with high awareness of mental health values, encourages the development of positive habits and strengthens family resilience in the face of social challenges. Therefore, this documentary will showcase the interconnectedness of social well-being, education, and the sustainable achievement of SDG 3 by focusing on mental health and family wellness. A study titled “Designing Behavioral Mental Health Rehabilitation” (Lie & Aulia, 2024) highlights that North Sumatra, particularly the city of Medan, records higher rates of mental disorders compared to the national average according to WHO Asia-Pacific. Approximately 7.9% of Medan’s population experiences depression, significantly above the national average of 3.7%. The study also reports that 6.3% of the population suffers from psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, a number far exceeding the global average, which typically remains below 1%. These alarming statistics are not matched by the availability of adequate mental health services; about 90% of Indonesia’s population lacks access to mental health care (Lie & Aulia, 2024). In the context of Batak Toba mental health, psychological pressure arises not only from external factors but also from deeply rooted cultural traditions. The Batak community continues to uphold the principle of the “3H values”: Hamoraon (wealth), Hagabeon (lineage), and Hasangapon (honor). These three values serve as benchmarks of social status and symbols of success in Batak society (Pudjiati et al., 2021). They are passed down through generations via formal education, customary institutions, and family teachings, shaping a collective mindset about what constitutes a ‘perfect life.’ On the other hand, these same values can become sources of social pressure when individuals are unable to meet them. Education is one of the pillars of life for the Batak community, not only as a means of intellectual advancement but also as a gateway to success. Educational principles and moral values are often instilled by parents from an early age, beginning at home. These values are sometimes passed down based on unwritten traditions linked to lineage. One notable principle in Batak culture is a deeply meaningful saying: “Anakkon hi do hamoraon di au,” which translates to “My child is my most valuable treasure.” This belief has long been passed down within Batak families. In the context of education, this principle serves not only as a parental motivation but also as a form of respect shown by children to their parents. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) publication on the Ethnic Group and Regional Language Diversity Profile from the 2020 Population Census Long Form, the Batak ethnic group holds the highest percentage of university graduates in Indonesia, accounting for 18.02%, followed by the Minangkabau ethnic group at 18.00%. Meanwhile, the Javanese come in eighth at 9.56%, and the Madurese last at 4.15%. Additionally, research from Kompas Research & Consulting (2022) revealed that 74% of Batak parents prioritize formal education for their children. Batak culture is widely known for promoting values such as hard work (hamoraon), academic achievement (hasangapon), and devotion to family (somba marhula-hula). However, amid modernization, these traditional values often clash with individual aspirations, non-traditional career paths, and the personal identity searches of younger generations. This tension is not unique to the Batak community, but the Batak offers a compelling and emotional lens through which to examine the struggle between heritage and modernity. Higher education and academic success are seen by Batak parents as expressions of love and sacrifice for their children, as well as investments in their children’s future. There is a strong sense of optimism that children will lead better lives, earn societal respect, and uphold the family’s good name, despite the high expectations placed upon them. Many Batak parents believe that supporting their children’s pursuit of a stable education is a declaration of love and a desire to see them thrive, feel secure, and be respected in a constantly changing world, not merely a matter of pride. However, in the midst of modernization and globalization, young Batak descendants, especially those born and raised in urban cities like Jakarta are often struggling between fulfilling family expectations and pursuing their own passions. This inner conflict is not merely a personal story but also a reflection of a larger social struggle surrounding identity, cultural expectations, and self-discovery in an evolving world. This documentary explores the relevance of these cultural and social issues in today’s context, aligned with the shifting values of urban Indonesian society. The growing awareness of mental health is a key focus in the film, as younger generations increasingly recognize the importance of mental well-being and resist life paths shaped solely by external expectations without regard for personal happiness (WHO Indonesia, 2022). Through the lens of Batak culture, this documentary highlights one of the many social changes taking place: how traditional communities in Indonesia must renegotiate their values in light of modern dynamics. The urgency of this documentary lies in capturing the ongoing cultural transformation, particularly the tension between inherited family values and modern individual dreams. It aims to provide an open dialogue between generations through the voices of Batak children and their parents. The goal is not to incite debate but to foster understanding of fears, hopes, and aspirations on both sides. This film intends to serve as a source of validation and

Leftovers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8yyFKMS_ko Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are 17 global goals, all of which aim to create a better world. The film Leftovers will focus on SDG Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, specifically discussing food waste and organic wastemanagement. The choice of Goal 12 is based on our concern and awareness of the low level of public consciousness regarding wise and responsible food consumption, which undeniably affects both the environment and human health. Waste remains a significant global issue that has yet to be effectively resolved. According to the National Waste Management Information System (SIPSN) data from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), Indonesia generated around 33.79million tons of waste in 2024, with 39.36% of that being food waste. This type of waste is the largest contributor to the national waste composition, with households as the main source (50.8%), followed by traditional markets (16.67%) and commercialbusinesses (11.01%). Based on the UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2024, Indonesia is the largest generator of food waste in Southeast Asia, producing around 14.73 million tons per year, and ranks among the top five globally in terms of food waste generation.The high volume of organic waste in Indonesia is driven by excessive and irresponsible food consumption habits. People tend to buy more food than they need, leading to leftovers that are ultimately discarded. These leftovers become organic waste that requires further processing. However, organic waste management in Indonesia remains inadequate. According to KLHK data, only about 15% of the total organic waste is reused to make compost or biogas, while the rest is directly sent to final disposal sites (TPA). The Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas) even estimates that, without policy intervention, Indonesia’s food loss and waste (FLW) could reach 112 million tons per year, or the equivalent of 344 kg per capita per year—meaning one person in Indonesia could waste almost 1 kilogram of food per day. The economic impact of this food waste is staggering, reaching IDR 213–551 trillion per year, or about 4–5% of Indonesia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Beyond the economic impact, food waste is also a major contributor to the climate crisis: on average, 7.29% of annual greenhouse gas emissions come from discarded food. The energy content of this wasted food could feed 61–125 millionpeople, or around 29–47% of Indonesia’s population—an irony, considering the country still faces high rates of hunger. The low public awareness about responsible consumption, combined with the challenges of recycling organic waste, contributes to Indonesia’s persistently high waste volume. Therefore, through the film Leftovers, we want to show the world thatseemingly simple and trivial everyday behaviors can actually have a significant impact on the environment. These are issues we could have prevented or minimized, but due to a lack of attention and education, we often fail to see them as part of ourresponsibility. Through this documentary, we aim to portray the journey of food from the dinner plate to the waste processing site. We will illustrate how food waste is handled by workers in the field—including the challenges they face—while educating the public that responsible consumption is a concrete step anyone can take. Because every leftover on the table carries a footprint and a burden that the Earth ultimately has to bear. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion

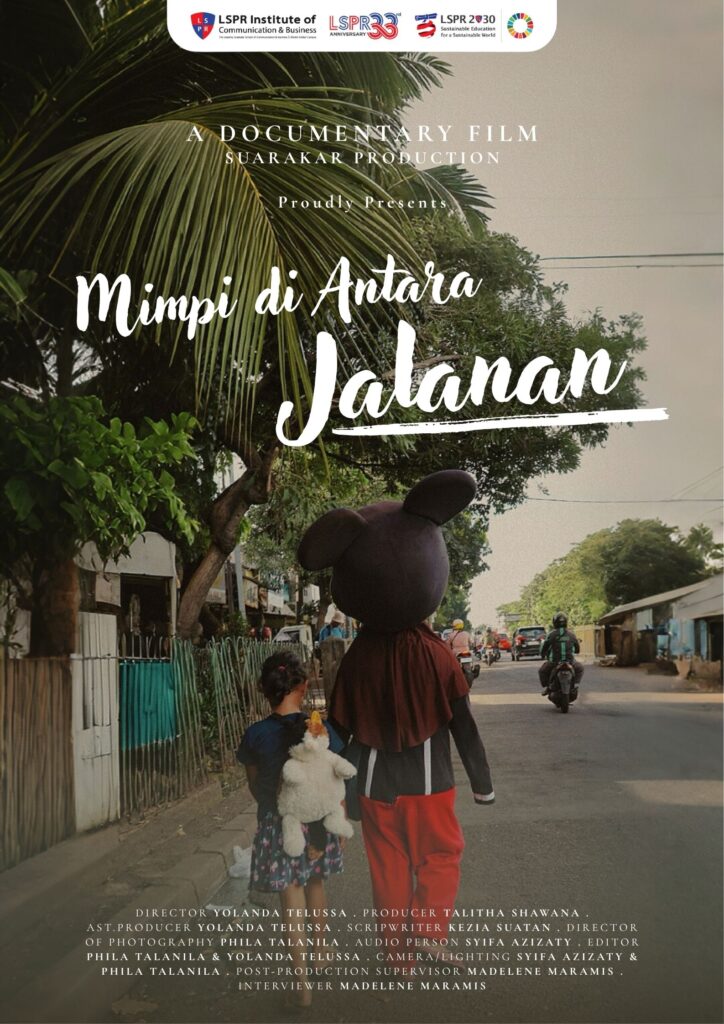

Dreams Among The Street

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eDLjQbv5NTI The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 global goals established by the United Nations in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure peace and prosperity for all by 2030. One of the SDG points, Goal 4 — Quality Education — focuses on inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all. Education serves as a fundamental pillar in fostering a progressive and competitive society. It plays a vital role in shaping individuals and empowering communities to thrive in an ever-evolving world. However, in Indonesia, equitable access to quality education remains a significant challenge, especially in underdeveloped areas of Jakarta. The gaps in educational infrastructure, facility availability, and access to qualified teaching staff present major obstacles to achieving a comprehensive vision for quality education. Bridging these gaps is crucial to ensure that every child, regardless of geographic location or socio-economic background, has the opportunity to benefit from a strong educational experience. Only by addressing these barriers can Indonesia nurture a well-educated population capable of contributing to the nation’s growth and global competitiveness. On January 24, we commemorated International Day of Education. The date was officially designated during a United Nations General Assembly in 2018, and serves as a reminder for all countries to build inclusive and equitable education systems at all levels. Despite this commemoration, many Indonesian children still cannot attend school. According to Statistics Indonesia (BPS), children not in school are defined as individuals of school-age who are no longer enrolled in formal education. For example, those aged 16–18 who have graduated from high school or equivalent are still considered “in school.” This indicator is based on the age at the start of the academic year. Over the past 5 years, the proportion of children aged 7–12 not in school has remained stable at around 0.6%. This trend continued through 2023 and 2024, with a percentage of 0.67%, highlighting a consistent pattern of educational exclusion for this age group. For ages 16–18, from 2020 to 2021, there was a decrease from 22.31% to 21.47%. However, in 2022 it rose again to 22.52%. In the last two years, this rate dropped to 21.61% in 2023 and further to 19.20% in 2024. This data has motivated SUARAKAR PRODUCTION to choose SDG Goal 4: Quality Education, observing the gap in educational access still occurring in Indonesia, even in large cities like Jakarta. Despite limited facilities, Yayasan Bina Anak Pertiwi is living proof that quality education can bring hope and opportunity to underprivileged children through a supportive and inclusive learning environment. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion

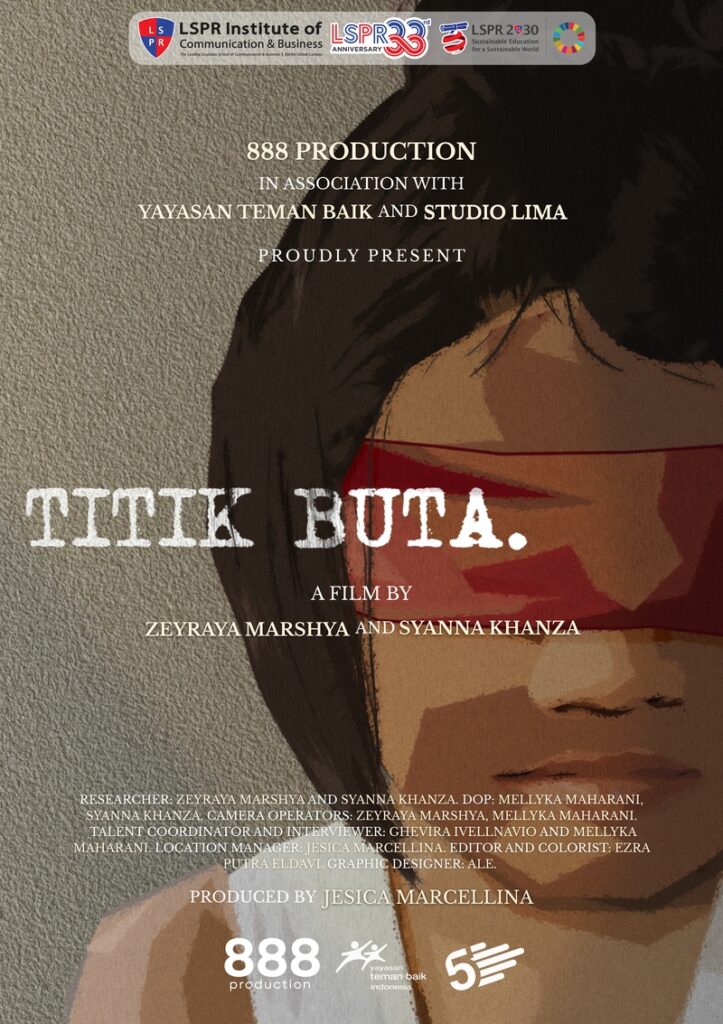

Titik Buta

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AR8wAHMhVwk Children are the future generation of a nation and should grow up in a safe, healthy, and nurturing environment. However, the harsh reality remains—violence against children, whether physical, emotional, sexual, or in the form of neglect, continues to be a critical issue in many parts of the world, including Indonesia. This form of abuse often occurs behind closed doors—in households, educational institutions, and social environments that should serve as protective spaces. Child abuse is a serious issue with long-term consequences on a child’s physical, emotional, and mental development. It includes physical violence, psychological abuse, sexual exploitation, and neglect, often perpetrated in the child’s immediate surroundings such as at home, in school, or within the community. According to data from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), approximately one billion children worldwide experience some form of violence—physical, emotional, or sexual—every year (UNICEF, 2020). In Indonesia, the Indonesian Child Protection Commission (KPAI) reports a continuous increase in child abuse cases annually. In 2023 alone, KPAI received over 2,000 reports of child abuse, the majority of which occurred within the family environment. This phenomenon reflects both the failure of the child protection system and the lack of public awareness regarding the importance of a safe and healthy upbringing for children. This issue is closely aligned with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) No. 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. One of the targets under this goal is to reduce violence and related deaths, and to ensure the physical and mental health of children. Efforts to address child abuse are a critical component of achieving the SDGs, as children are the foundation of a nation’s future. Through the documentary film “Titik Buta” (Blind Spot), we aim to amplify the often-unheard voices of children who are victims of violence, as a form of advocacy and a call to action for society to build safer and more compassionate environments. This film is intended not only as an informative medium, but also as a tool for education and public campaigning to help break the cycle of violence against children. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion

Between Two Lands

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wi7cs0h4nNw Sustainable development has become a key focus for many countries, including Indonesia, aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). One of the major challenges in metropolitan cities like Jakarta is the inequality in living standards across neighborhoods, especially between dense, low-income settlements and revitalized areas such as community-based vertical housing. In Kelurahan Menteng Atas, Setiabudi District, lies RW 13, a densely populated area with around 1,522 residents living on just 5,000 square meters of land. Due to economic limitations, it’s common for multiple families to share one small house. This overcrowding creates various issues from lack of access to basic services and poor sanitation leading to health risks, to high rates of violence. The presence of RPTRA (Child-Friendly Integrated Public Spaces) Kebon Sawo since 2017 has brought some positive changes, but many challenges remain. In contrast, Kampung Susun Akuarium stands as a successful example of community-based revitalization. After enduring forced evictions and prolonged advocacy, this community was rebuilt and has won awards across the Asia Pacific for its participatory, sustainable urban development approach. The co-design model empowered residents to take part in planning and rebuilding, proving that revitalization can be a form of empowerment, not just physical relocation. Still, transitioning to vertical living presents new challenges: adapting to unfamiliar structures, losing social bonds, and adjusting to new norms. Meanwhile, those who remain in dense settlements view their social solidarity and emotional ties as irreplaceable. Through this documentary, we aim to capture life in both communities, the ones who stayed, and those who moved to show that the concept of “home” is more than just a building. It holds stories, conflicts, hopes, and social identity. We hope this film becomes a reflective mirror for the public and policymakers to understand the importance of improving urban living, health equity, and building inclusive cities for all. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion

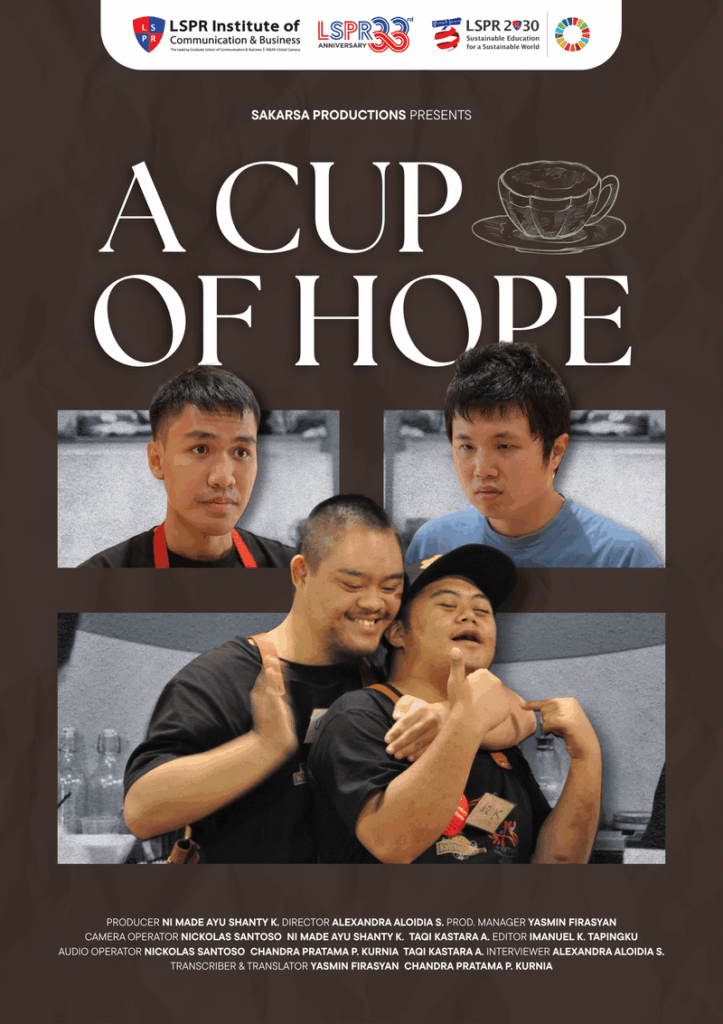

A Cup of Hope

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fmq0N5TyZ3A Building inclusive employment opportunities is a form of social service that plays a crucial role in realizing equality, especially for individuals with special needs. However, negative stigma toward people with disabilities remains a significant challenge in Indonesia. Discriminatory behavior is still prevalent in society, where they are often perceived as incapable of working like typical employees. Many foundations and Special Schools (SLB) have made efforts to combat this stigma by providing training programs for children with special needs to prepare them for the workforce. Ucu Rahayu, head of the Cahaya Batin Social Institution for the Blind and Hearing-Speech Impaired (PSBNRW), expressed concern over how people with disabilities are still underestimated, even though some of their beneficiaries work as civil servants (ASN) and also have special needs (Pratama et al., 2024). Yet, this issue continues to receive insufficient attention, as seen in the limited number of inclusive workplaces in Indonesia. Many employers still hesitate to fully trust individuals with disabilities (Aji, A.L.D., et al., 2017). In reality, the inclusion of persons with disabilities in Indonesia’s workforce is unavoidable. Unfortunately, the majority of them still face discrimination in gaining employment opportunities (Widhawati, M.K., et al., 2019). According to data from Statistics Indonesia (BPS) in 2022, over 17 million people with disabilities were of working age. However, only around 7.6 million of them had obtained jobs in either the formal or informal sectors. In the previous year, 2021, only 5,825 people with disabilities were recorded as employed—1,271 in state-owned enterprises (BUMN) and 4,554 in private companies (Retnoastuti, 2024). These figures clearly show a lack of accessibility and persistent negative public perceptions, even though the government has established protections under Law No. 8 of 2016 on Persons with Disabilities. This issue is not only a national concern but also a deeply rooted dilemma Indonesia faces in its journey to build an inclusive and equitable society. In the social dimension, people with disabilities continue to be victims of stigma and discrimination, and are often excluded from access to quality education and employment. One of the main barriers to providing an inclusive work culture is limited accessibility and a sceptical mindset. Some companies are still unwilling to hire people with disabilities due to assumptions about lower productivity or concerns about additional costs (Putra, 2019). However, with proper guidance and a supportive work environment, people with disabilities can quickly demonstrate their potential and make meaningful contributions. Much more must be done by the government, communities, and even the media to address these disparities. With the right approach, it is possible to raise awareness and drive a paradigm shift toward a more inclusive workforce. This documentary, produced by Sakarsa Productions, highlights a key theme from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs are a set of 17 interconnected global goals adopted by United Nations Member States in 2015 as a universal call to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure peace and prosperity for all by 2030. The documentary titled Secangkir Harapan (A Cup of Hope) is based on SDG 10: Reducing Inequality. We believe that one of the most effective ways to raise awareness and empathy toward the lack of inclusive employment is by directly highlighting the issue, spreading knowledge, and showing the public that workers with disabilities are capable of learning and contributing in the professional world. As mentioned earlier, they possess diverse abilities, which can be nurtured with appropriate support. Through the use of media—particularly documentary film—we aim to help reshape public perception. A documentary does more than deliver information; it offers a vivid and emotionally resonant depiction of reality. This medium can serve as a powerful message to the public that our friends with disabilities have the same capabilities as anyone else and are equally entitled to opportunities. Through Secangkir Harapan, we hope to open new perspectives and encourage society to give people with disabilities the attention and opportunities they deserve—not as subjects of pity, but as equals. More than just a visual presentation, this documentary aspires to be a small yet meaningful step toward building a more inclusive and just society and workforce. THE LAST BATH Craving Pathway To Recover Coin Of Tears Cultural Erosion